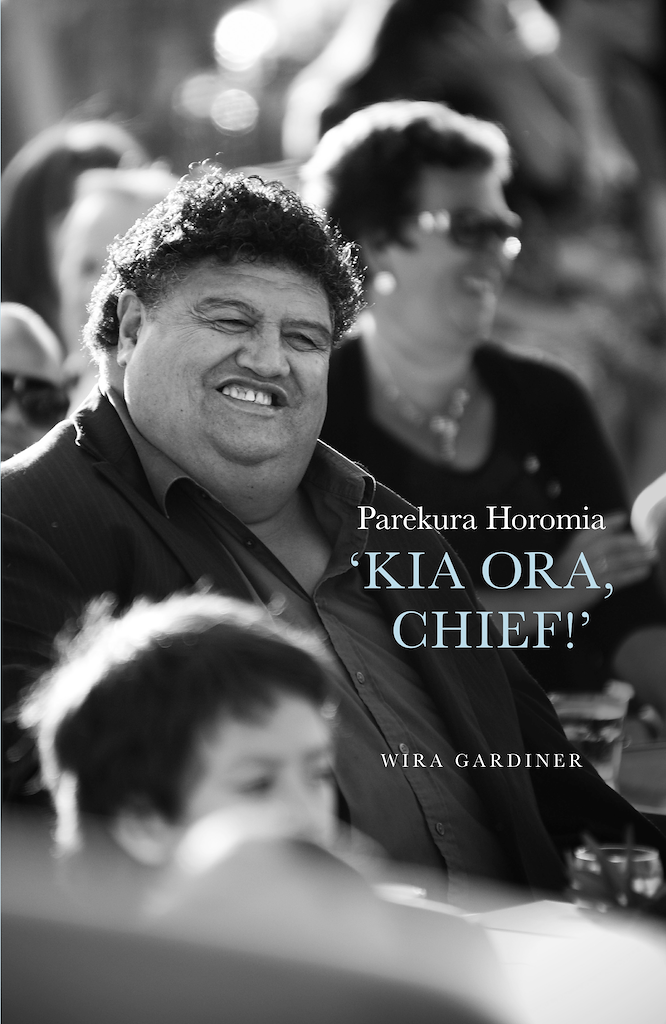

Ko ‘Kia ora Chief’ he haurongo hou o te tangata kaitā, te Minita mō ngā take Māori o mua, arā ko Parekura Horomia. I tuhia tēnei haurongo e te Toihautū o mua o te tari kāwana o Te Puni Kōkiri, arā ko Tā Wira Gardiner.

Kua kōrerotia e Kōkiritia ki i a ia mō ngā mahi rangahau i mua i te tuhinga o te pukapuka nei me te whakaputa i tētahi kōrero aukati mai i te pukapuka e matapakitia ana ki ngā mahi i whāia e Parekura i mua i tōna tūranga hei kaitōrangapū matua.

Published: Rāpare, 04 Hakihea, 2014 | Thursday, 4 December 2014

Kia ora Chief! Koinei te kōrero whakamihi i kaha mōhiotia ai a Parekura Horomia, te Minita Māori o mua i mate atu rā i te marama o Paenga-whāwhā i tērā tau.

Ināianei koinei te ingoa kua whiriwhiria mō te pukapuka kua tuhia mōna ka whakarewatia ki Uawa hei te paunga whitu e kainamu nei, ki te Whare Paremata hei te wiki e tū mai nei hoki. He pukapuka tēnei mō tōna oranga – mai i tōna tipunga ake i te Tairāwhiti, te maha noa atu hoki o āna kaupapa mahi, tōna umanga tōrangapū, tae atu ki tōna tangihanga i Uawa i huihui ai te tini tangata kanorau e whakapaetia ana āhua 12,000 te rahi.

E ai ki a Tā Wira Gardiner, ko tētahi hoa pūmau nōna, ‘kaipatu ahi’ hoki, i takea mai te pukapuka i te tau 2006.

“I kī atu ahau ki a Parekura, ‘me tuhi pukapuka tētahi tangata mōu, nā te mea he tauira koe o te tūmanako kua tutuki,” ko tā Wira whakamahuki.

“I tono mai ia kia tuhia e au, ā, ka mea atu au ‘Āe, māku e tuhi engari me pānui au i ō rātaka me āu tuhinga katoa’. Heoi anō, tino kore nei āna mea pērā. He kauhau āna, engari kāore ia i tuku.”

Nō Wira te whakaaro kia whakapau taima a Parekura ia rā – he meneti torutoru noa iho – ki te kōrero ā-waha kia kapohia ai āna kōrero kia tuhia ai whai muri mai. ‘Waiho māku,’ te whakautu a te Minita i taua wā, engari kāore rawa i tutuki. Nō te tau 2011, whai muri mai i te pānonitanga o te Kāwanatanga, i kī atu ia ki a Wira kua rite ia kia tuhia taua pukapuka.

“I mea atu au ki a ia ‘Kao. Kua pūrari tūreiti kē. Me he niu pepa tākai ika parai noa iho koe ināianei. Nō inanahi kē tāua.

“Whakamā katoa au mō tērā. Nā, poroporoaki ana au i a ia i tōna tangihanga, ko taku kī taurangi ki āna tama ka tuhi pukapuka au mōna. Nāku anō au i here kia ū ki te kaupapa mā te kī atu ka oti te pukapuka hei mua mai te hura kōhatu. Nā, kotahi tau ki te 18 marama pea te roa o te wa māku.”

Ki tā Wira kōrero ko te mea uaua i te tīmatanga o te mahi, kāore he tangata i pīrangi ki te kōrero ki a ia.

“He mōata rawa, ā, kāore anō rātou kia rite ki te kōrero mai mōna. Otirā, tata ki te mutunga o te tau i tīmata rātou ki te whakaputa mai i ngā kōrero.”

I te tau nei ka mahia te nuinga o ngā uiuitanga āhua 70 te nui – kotahi haora pea te roa o ia uiuitanga – i mua i tā Wira mahi tuhituhi mō ngā marama e whā, e 5 ki te 10 haora ia rā ka pau ki te tuhi.

Ki a Wira, mō te aroha noa tēnei mahi, ā, i mahia te tuhituhi i waenga i āna mahi poari tino maha. Mā ngā mokopuna a Parekura ngā moni katoa ka kohikohia i te hokonga atu o te pukapuka hei pūtea whaiwhai mātauranga.

I ako rānei ia i ētahi kōrero hou mō taua tangata i mōhio ai, i mahi tahi ai ia i ngā tau 30 kua taha ake nei?

“Ko tōna tino tūmataiti. He kaha ia ki te whakamarumaru i tōna oranga, ki te hunga e tata ana ki a ia hoki. Nā, i mōhio kē au mō te nuinga o tōna oranga, engari 30% pea kāore au i mōhio. Arā ētahi āhuatanga o tōna oranga i ohorere ai au. He piko, he uiuitanga, he mea hou ka puta.

“Engari ka riterite tonu ngā kaupapa i ahu mai. I pērā hoki i tōna tangihanga. Ka tū tētahi tangata ki te kōrero mō Parekura, kātahi ka katakata te katoa i ō rātou ake mōhiotanga mō taua kōrero engari he rerekē atu ngā ingoa, te wā hoki. Ka taea e ia te hono atu ki tangata kē i ā rātou pāhekoheko, taunekeneke hoki ki a ia,” te kī whakakape a Wira.

I roto i tēnei wāhanga i tīkina mai i Kia Ora Chief (nā Huia), ka tirohia e Wira te ara i whāia e Parekura kia tū ia hei kaimahi matua i ngā tari kāwanatanga.

Extract from Kia Ora Chief

On face value, it is hard to imagine how Parekura became a senior bureaucrat. While there was no doubting his energy and determination, he certainly did not fit the image of a public servant. He lacked formal qualifications. His physical presentation was intimidating and unkempt, and his ability to express himself clearly and succinctly was limited. An unusual set of circumstances was required to catapult Parekura into the limelight; that and a special kind of senior bureaucrat, who was willing to look past these obvious deficiencies.

Parekura at GELS office, Department of Labour, Charles Fergusson Building, 1984 Source: Horomia whānau

The set of unusual circumstances took the form of the sweeping set of economic reforms ushered in by Roger Douglas[1] the Minister of Finance for the Fourth Labour Government. ‘Rogernomics’, as these policies became known, saw wholesale restructuring of the way in which government delivered services. By and large, rural New Zealand and the more isolated areas of Northland and the East Coast bore the brunt of these changes. On the East Coast, there were massive job losses in forestry, the Ministry of Works and other state agencies. To counter the job loss and the lack of opportunities for employment, the Labour Government introduced a range of employment schemes.

In 1978, Parekura returned to Tolaga Bay and got involved in farming, fencing, shearing, land management and a range of other community activities, including representing the New Zealand Māori Council at the local level. In 1978 and part of 1979, he worked with Boydie Donald’s[2] shearing gang. Boydie recalls that ‘he could shear a reasonable number of sheep in a day; his tally would have been about 300 sheep’.

Parekura’s first mission on returning to Tolaga Bay was to get back the farm, which had been sold by his Nanny, Mum Jane.[3] Alice (Tuppence) Smith[4] explained that her parents gave her the farm as a wedding present, but because of a violent marriage, she did not want to stay and moved to a house in Tolaga Bay. Mum Jane then sold the farm to a local for a token sum. Parekura went to the Māori Land Court to get the farm back. He was in his early 30s when he succeeded. Tuppence recalled that this was just before he started work with the Department of Labour. The land on which the house stood and the land around it belonged to his grandfather, Poneke (Nunu) Waikari.[5] Other parcels of land belonged to Nanny Sue Kirikiri[6] and other relations. The shareholders all agreed to give the land to Parekura, and he had won the first of many battles he was to wage over the next decade to take back control of Hauiti lands.

1997 CEG conference, Tikitere, Rotorua L-R John Bishara, Parekura, Dave Wilson, Richard Brooking, George Kahi, Hemi Toia. Source: Horomia whānau

By the early 1980s, he was employed by the Department of Labour as a Supervisor for the Project Employment Programme (PEP)[7] schemes for unemployed workers.[8] The PEP scheme began in August 1980 and ran for six years until August 1986, although it continued beyond this time in some rural areas, including the East Coast as a consequence of damage caused by Cyclone Bola in 1988. The scheme was designed to give subsidised, short-term public sector employment for job seekers who were at risk of becoming long-term unemployed. Parekura led work gangs throughout the East Coast on a variety of community enhancement projects ranging from chopping and providing firewood for older people to marae renovation projects. The PEP schemes were a heaven-sent opportunity for isolated communities throughout the country to renovate marae and complete other long-standing tasks. Workers on these projects learned basic carpentry skills, and some even became competent carvers. Just as importantly, they learned basic job skills, such as getting up each day to go to work and participating in positive community activities.

The second significant event that catapulted Parekura into greater prominence in the eyes of senior bureaucrats in Wellington was Cyclone Bola, which hit the East Coast in early March 1988. Cyclone Bola was one of the most destructive cyclones to ever hit New Zealand. As it moved over the Hawke’s Bay and East Coast, it slowed, and for three days, it dumped a huge volume of torrential rain on the region. Some of the worst-hit areas lay inland from Gisborne, ‘winds forced warm moist air up and over the hills, augmenting the storm rainfall. In places, over 900 millimetres of rain fell in 72 hours, and one area had 514 millimetres in just a single day.’[9] The floods that followed destroyed houses, crashed over stopbanks, swept away bridges, fords and roads and gouged out large sections of forested hillsides. Part of Gisborne’s water supply system was destroyed. There were three fatalities in Mangatuna. Thousands of people were evacuated from their homes in Gisborne and some hundreds in Wairoa and Te Karaka.

Ray Taylor[10] was heavily involved with recovery work resulting from the cyclone. He was the main point of contact for the Department of Labour. He and Parekura were responsible for organising 300 PEP workers, who turned up the day after the storm. The workers assembled at the Railway Reserve, Gisborne. The Department of Labour funded all the gear, the wages and the work vans. Parekura’s extensive network throughout the East Coast, his no-nonsense reputation and his links to key organisations, such as the New Zealand Māori Council and the Māori Women’s Welfare League, contributed to his growing reputation as a fixer and go-getter. He was someone who could get things done. He was 38 years of age. He had demonstrated that in times of great emergency and crisis, he could make things happen. This would have impressed the senior officials of the Department of Labour.

When I interviewed Mike Williams[11] who was President of the Labour Party from 2000 to 2009, he told me of a conversation he had with Parekura about the impact of Cyclone Bola on the East Coast. Parekura told Mike that the response to Cyclone Bola was the best thing that had happened to the East Coast in his lifetime. He said everyone had a purpose, and everyone had jobs. There was massive clean up, and the young people were heavily involved. They had money in their pockets. They got a taste of what it was like to work, and they started to have ambitions. And he asked, ‘Why can’t governments create Cyclone Bola situations?’

***********

[1] Hon Sir Roger Owen Douglas, Minister of Finance, Lange’s Labour Government, 1984–1988, architect of a set of radical economic policies known as ‘Rogernomics’

[2] Boydie Donald, interview 26 May 2014

[3] Mum Jane (Smith) Waikari, Parekura’s grandmother, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu

[4] Alice (Tuppence) Smith, interview 20 March 2014, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu

[5] Poneke (Nunu/Duke) Waikari, Parekura’s grandfather, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou

[6] Te Huinga Kirikiri, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou

[7] Robert J. Gill, New Zealand Department of Labour, Occasional Paper Series, page 30

[8] Liz McPherson, notes, 29 April 2013

[9] www.gisborneherald.co.nz, 5 October 2007

[10] Ray Taylor, joined the Department of Labour in 1983; with Parekura, he coordinated the work force for Cyclone Bola recovery work in 1988

[11] Mike Williams, interview, 10 March 2014